The following comes to us, compliments of Google Translate, from the Argentinean weekly Perfil (“Profile”).

The abstract whole

In compensation, he dedicates some positive adjectives to him and ends with a strange comparison between Ashbery and Berdiaev.

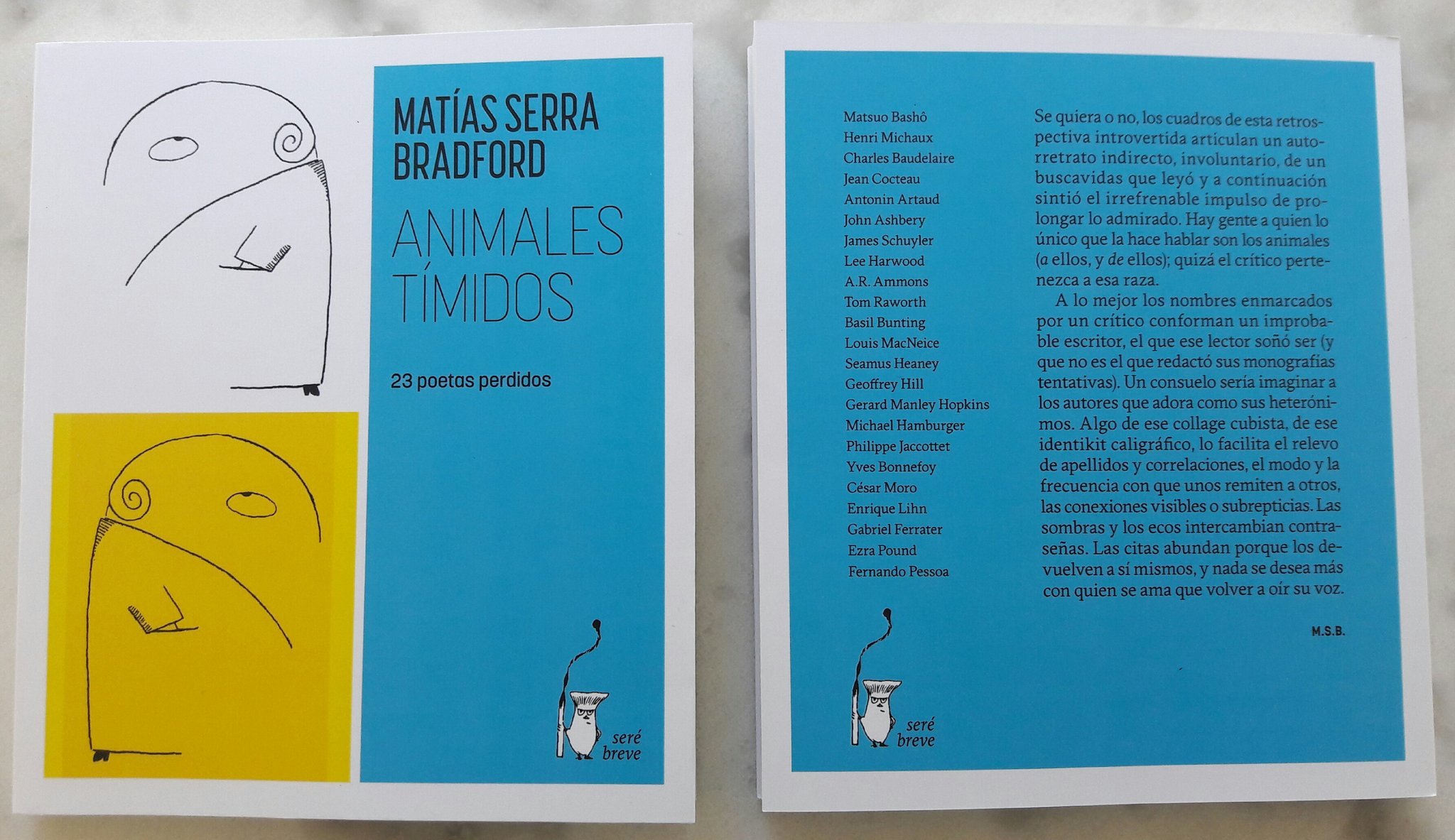

Reading Matías Serra Bradford's essay on John Ashbery, included in the recently published Shy Animals. 23 Lost Poets (Ediciones Seré Breve, Buenos Aires, 2021), it occurred to me that perhaps a brief and incomplete story of Ashbery's critical reception among us could be made, a little like that, randomly, at the fly of a bird (Can You Hear, Bird). Surely I should start around the 90s, years in which a group of poets began to read, quote and translate Ashbery abundantly, to the point that I myself met him thanks to the recommendation of one of them (Andi Nachón, in the horrible bookstore of El Corte Inglés, in Seville, where I bought Self-portrait in Convex Mirror, translated by Javier Marías, in the Visor publishing house, a translation that still seems to me the best of those I read). But no, it is better to go back to 1969, in which 15 American poets appear, with translation and introduction to each poet by Alberto Girri (Bibliographic Publishing House, Omega collection, Buenos Aires). Girri almost reluctantly translates four poems (including some crucial ones in Ashbery, such as The Painter and The Instruction Manual, which had already been translated before by Ernesto Cardenal) and writes an even more reluctant introduction, in which, first, he transcribes some definitions of Ashbery ("I try to use words abstractly, as an abstract painter would use painting Finally, as compensation, he dedicates some positive adjectives to him and ends with a strange comparison between Ashbery and Berdiaev. Obviously, when Girri didn't like an author he had to translate, he made it very clear.

Now we do reach the 90s, issue 19 of Diario de Poesía (August 1991) which includes an excellent dossier on Ashbery - with impeccable translations of poems, interviews and a conference that works well as a poetic ars, called "The invisible avant-garde". In the introduction to the dossier, Carlos Basualdo writes: "Ashbery has built a splendid conjectural poetry, which often achieves its highest tones while bordering a deliberate grayness, an exasperating consciousness that grants nothing to hopelessness or despair. The danger of this position - ethical, aesthetic - was complacency with himself, with his own sagacity; Ashbery conjures it most of the time (...) against the heroic poet, Ashbery builds this image of an antihero who does not bring his 'interior' but his mere estrangement as a gift (...) the poet is neither a prophet nor a fortune teller, he does not reveal the future or the secret meaning of the universe, because there is possibly no such secret meaning, there is nothing behind the veil.

Already in the present, in The Dong with a Luminous Nose: Ashbery, the essay included in the aforementioned book, Serra Bradford rightly notices Ashbery's phrase in which, "when commenting on another poet," he is actually talking about himself: "We rarely know exactly what happens, but we get a strong impression of how it happens." A little earlier, Serra Bradford had hit the nail on the head: "It's not that the poet is uneven; it's that his poems slide over the irregular. He does not seek to find ideas; these are the result of the accidental (...) Every sentence of Ashbery is precise but the whole remains somewhat abstract."