From Stylus, the Poetry Room blog of Harvard’s Woodbury Poetry Room, Jeffrey Careyva, who has been charged with cataloging a collection of books from John Ashbery’s reading library, gives an account of his experience and an overview of its riches.

Published on March 22, 2023

ASHBERY-ESQUE: Adventures in Cataloging the John Ashbery Reading Library

written by Jeffrey Careyva

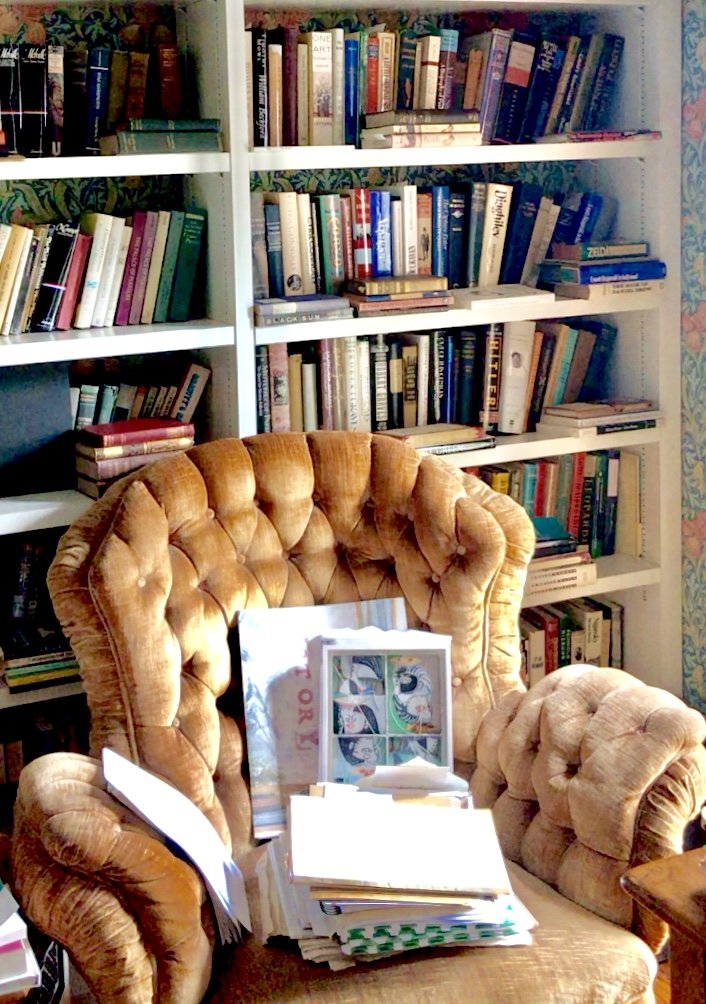

Cataloging John Ashbery’s book collection has been a massive undertaking. At least it has been for me, the English Department grad student who, book by book, leaves through the foxed pages that frame the background of Ashbery’s rich literary life. After processing over 2,500 books from his library in a mere nine months—roughly half of the collection, which was generously donated to the Poetry Room by David Kermani—Ashbery’s archived books have revealed some fascinating things about him, his peers, and maybe even about myself.

1. Self-Portrait as a Comprehensive Collector

One of the first lessons gleaned from the library is that Ashbery diligently collected some authors’ work to completion. A bookworm since his time at Harvard in the 1940s, John sought his own copies of collections by beloved influences like Marianne Moore and W. H. Auden, and he closely followed the decades-spanning careers of such friends as Kenneth Koch and James Schuyler.

Though Ashbery began acquiring books as early as his late teens, according to biographer Karin Roffman his more expansive collecting phase (which included frequent field-trips to local antiquarian booksellers with “assistants, former students, and friends”) gained momentum in the mid-1980s, after he and Kermani purchased a 4,000-square-foot home in Hudson, New York. With a whole house to fill, Ashbery could cover not only the literary bases he had missed in his youth but also venture further into the bibliographies of his lifelong favorites.

Thus, the Hudson collection runs long and deep. It includes multiple editions of classic Henry James works like The Ambassadors and The Wings of the Dove, for example, and a mountain of Anthony Trollope’s Victorian novels easily gives the collection its heft. And, of course, John comprehensively collected many poets: from John Dryden, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Gertrude Stein to Ted Berrigan, Wanda Coleman, Makoto Ōoka, Raymond Queneau, John Yau, and the Waldrops, to name a few.

As someone who is writing part of their dissertation on the variability of Ashbery’s poetic voice, I find the depth and breadth of the Hudson collection to be incredible. I could expect the presence of Ashbery’s New York School friends and acquaintances, some classics of Anglophone literature, and a slew of modern French poets, but what surprises me still is the diversity of genres, styles, and periods that Ashbery synthesized.

At this stage of cataloguing, I have been particularly awed by John’s keen interest in 20th-century British novelists.

Perhaps the first standout is his extensive collecting of the work of the English industrialist Henry Green, about whom Ashbery wrote his Columbia University Master’s thesis. A number of British queer writers are also particularly well represented, including: the novels and autobiography of the mercurial modernist Mary Butts; 20 novels by the fame-averse Ivy Compton-Burnett; and seemingly everything by or about the shy aesthete Ronald Firbank.

Indeed, although Ashbery is known as an American francophile, the Hudson library reveals his concomitant interest in the Brits, including extensive representation of the works of George Meredith, Evelyn Waugh, Elizabeth Bowen, Jean Rhys, and Barbara Pym. Moreover, Ashbery is a proven student of modern European and South American classics: the eccentric writings of Robert Walser, the pioneering magical realism of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, and such Russian mainstays as Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Vladimir Nabokov are all frequent presences.

As Ashbery supported himself as a writer, translator, and art critic between France and New York for many years, he needed to keep abreast of not only rising literary stars but also the canonization of authors we take for granted today. New York School writers frequently looked beyond America’s shores—Frank O’Hara, for example, iconically drew from the Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky—but the Hudson collection points to Ashbery’s long and almost systematic collecting of both niche and world-renowned authors.

2. The Fine Art of Inscribing

Based on the handwritten inscriptions Ashbery left in his books—a practice he discontinued in his middle years—I am also beginning to assemble a picture of the texts that were formative to his youth, or those that were at the very least of interest to him at the time. A range of texts that he procured in his twenties, including the Muir translations of Kafka (which he purchased soon after the first U.S. editions appeared), the Modern Library editions of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, and his beloved copy of F. T. Prince’s poetry, are each accompanied by the simple inscription “John Ashbery / Harvard” or “John Ashbery / New York,” along with the year he likely acquired them.

Being myself a 20-something lover of Kafka, Proust, and Prince studying at Harvard, coming across one of these volumes amid Ashbery’s vast collection is a special treat. Books like these represent the seeds of Ashbery’s adult literary interest and style, even if he never wrote as much prose as Proust!

Ashbery’s collection of poetry magazines, chapbooks, monographs, and anthologies seemingly —and expectedly—constitutes the most significant portion of his library, especially when only considering inscribed or annotated books. (Our cataloging efforts in this genre remain underway with well over 1,000 poetry books logged so far.) Between the first chapbooks of Language poets like Rae Armantrout, Elizabeth Willis, and Charles Bernstein and the posthumous collected works of such canonical figures as John Keats, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and Walt Whitman, the library’s spread of poetic styles is vast.

Alongside the many kinds of poetry Ashbery collected, there is also the impossible question of what each book ‘meant’ to Ashbery: a random purchase, a long-sought find, an invaluable inspiration, or memento from a dear friend? As the relationships among Ashbery’s books are still coming into view, one thing is already crystal clear: much of Ashbery’s contemporary poetry collection was given to him. From inscriptions and preserved pieces of mailing envelopes, we can surmise the hundreds and hundreds of gifts that Ashbery integrated bric-à-brac into his constantly evolving poetic atheneum.

One interesting thing I’ve learned is that despite poets’ creativity with language, when it comes to inscriptions many find themselves repeating a fixed dictum. Hundreds of Ashbery’s poetry volumes contain inscriptions with slight variations of “To John Ashbery, with great admiration and affection, [Poet]”. Sometimes however there is a date of inscription, and if you’re really lucky, a little drawing: maybe a cloud formation by Mark Strand or a bookish pig by Ciara and Ed Barrett. The latter made me smile on a rainy day working nearly alone in Houghton.

Some inscriptions, by such friends as Robert Creeley, Dara Barrois/Dixon (née Wier) and Gerrit Lansing, are more intimate and intricate. Lansing jests “from one ‘cult figure’ (as Ronald said) to….” Indeed, there is a through-line of playful affection that Ashbery appears to have inspired in a wide range of writers: from James Tate’s “Dear John, No. 1 in my book!” to John Tranter’s epigraph: “Hello, old bean, don’t you find The Tempest a little garrulous? Thinking of you, as ever, love, John.”

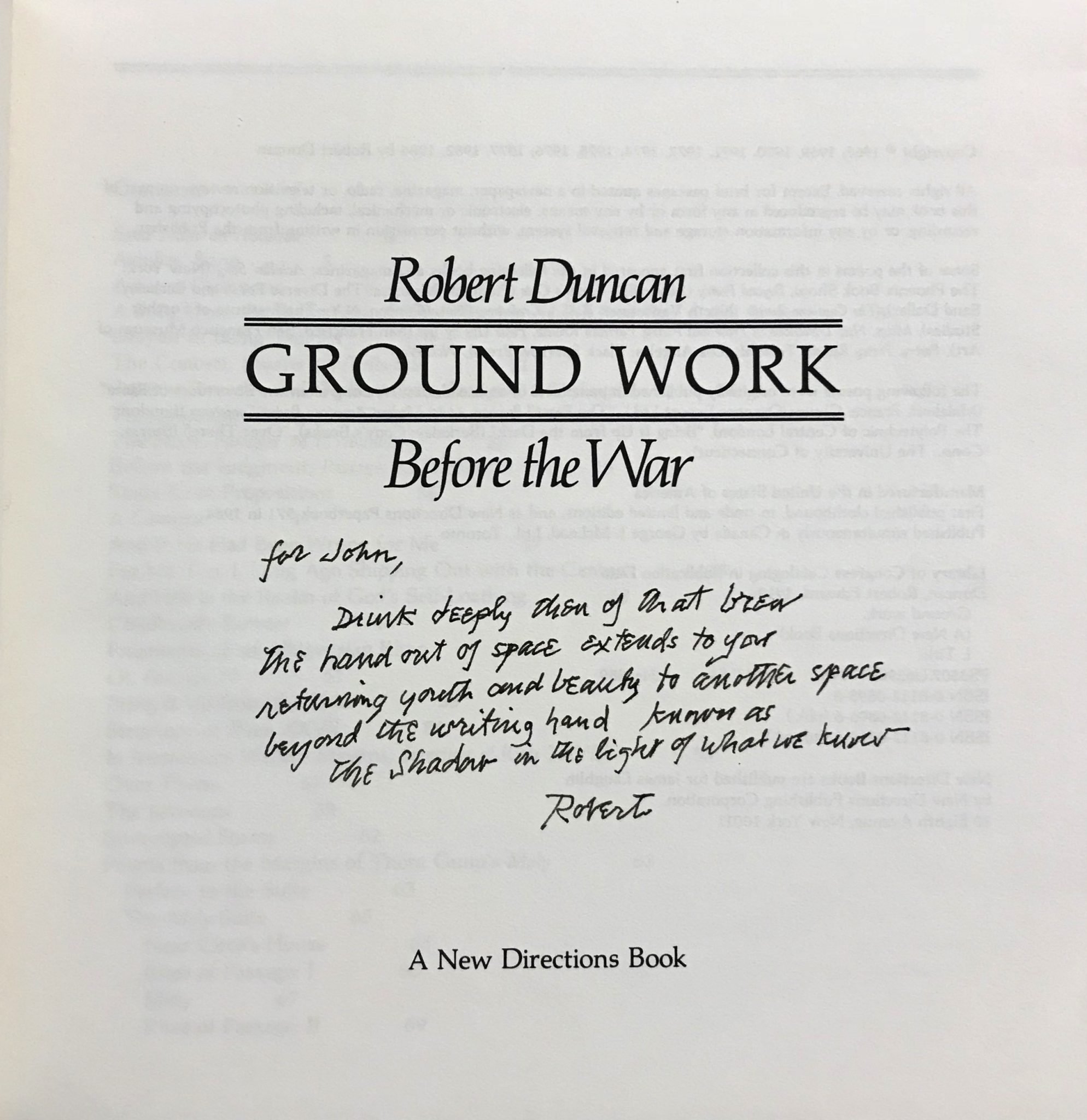

And, several inscriptions even rise to the level of original works: among them, Robert Duncan’s meditative lines: “Dear John, Drink deeply then of that brew/ the hand out of space extends to you/ returning youth and beauty to another space/ beyond the writing hand known as/ the Shadow in the light we knew.”

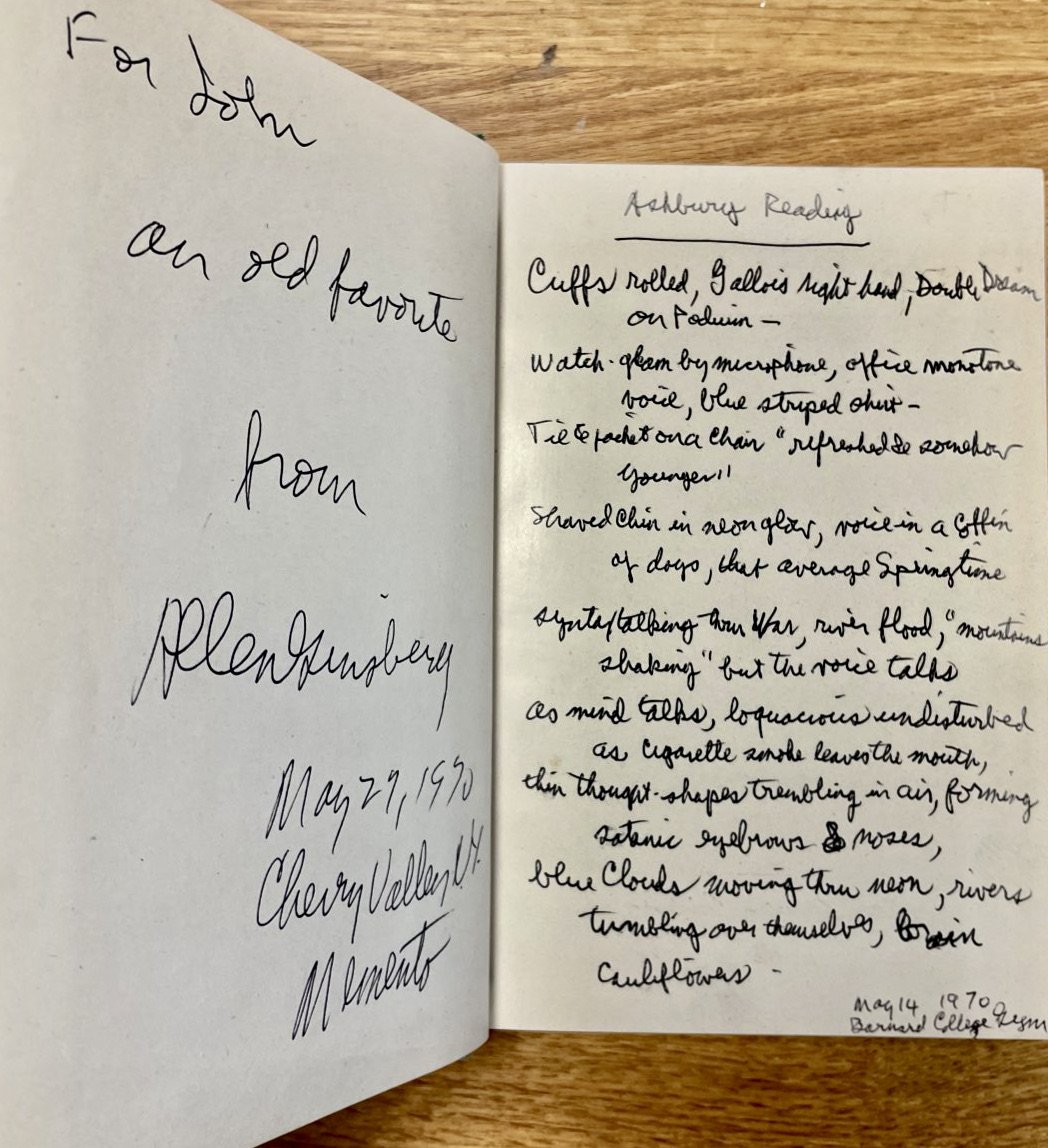

One of the most mesmerizing inscriptions comes from the hand of Allen Ginsberg. On May 14, 1970, Ashbery, Ginsberg, and Kenneth Koch participated in an evening reading at Barnard College to support the “Columbia Faculty Action for Peace Committee,” among other anti-war organizations. Two weeks later, Ginsberg appears to have given Ashbery a copy of Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s Maurine and Other Poems (1888), replete with a little message and a striking occasional poem.

ASHBURY READING [sic]

Cuffs rolled, Gallois right hand, Double Dream

on podium –

Watch gleam by microphone, office monotone

voice, blue striped shirt –

Tie & jacket on a chair “refreshed [he] somehow

younger”

Shaved chin in neon glow, voice in a coffin

of dogs, that average Springtime

syntax talking thru War, river flood, “mountains

shaking” but the voice talks

As mind talks, loquacious undisturbed

as cigarette smoke leaves the mouth,

thin thought shapes trembling in air, forming

satanic eyebrows & noses,

blue clouds moving thru neon, rivers

tumbling over themselves, brain

cauliflower –

May 14 1970

Barnard College [xxx]

Ashbery’s library is the material evidence of the reading habits that make up an astounding literary career. Already we have found a menagerie of gifts from close friends and admirers, required school books, eclectic purchases, and some clearly cherished volumes. With almost 2,500 books left to catalog, who knows whether another gift from Frank O’Hara (a Piranesi etching that Frank purchased with John in Paris has already been added to the Finding Aid) or a signed first-edition Auden lies in wait!

CREDITS: The photograph of the Hudson home of John Ashbery and David Kermani was originally published in “The Poet’s Hudson River Restoration,” Architectural Digest, June 1994, p. 44. All other photographs were taken by Christina Davis at Ashbery’s Chelsea and Hudson homes and during the cataloging process at Houghton Library.

FILED UNDER: Articles, Ideas & Discoveries

TAGGED WITH: ashbery, featured, ginsberg

by Jeffrey Careyva

Jeffrey Careyva (he/him/his) is a PhD candidate studying anglophone poetry and disability studies. He is a cataloger for the John Ashbery Reading Library and the co-manager of Child Memorial Library.